- Authors

This article is the first in the series Building applications using embeddings vector search and Large Language Models. In these blog posts I'll explain these concepts and the process of building a semantic document search pipeline. These materials are based on an internal documentation search tool and a talk I gave about it at Beryl.

To produce the posts from the recorded talk, I used Whisper.cpp to transcribe what I said and asked an LLM to clean up the transcription. Then I edited the text to add some missing bits and make it sound less like a robot 🤖. This was useful to prevent having to write from scratch, but I was a bit underwhelmed with the quality.

Welcome to this talk about large language models and embeddings. These are two related but distinct topics and tools in natural language processing. I have been interested in open language models and how to build applications with them, so I want to share some of my findings and tips with you.

Let’s start with embeddings and then move on to language models afterwards, as I think it will be easier to understand the more complex concepts behind LLMs if you already know what embeddings are.

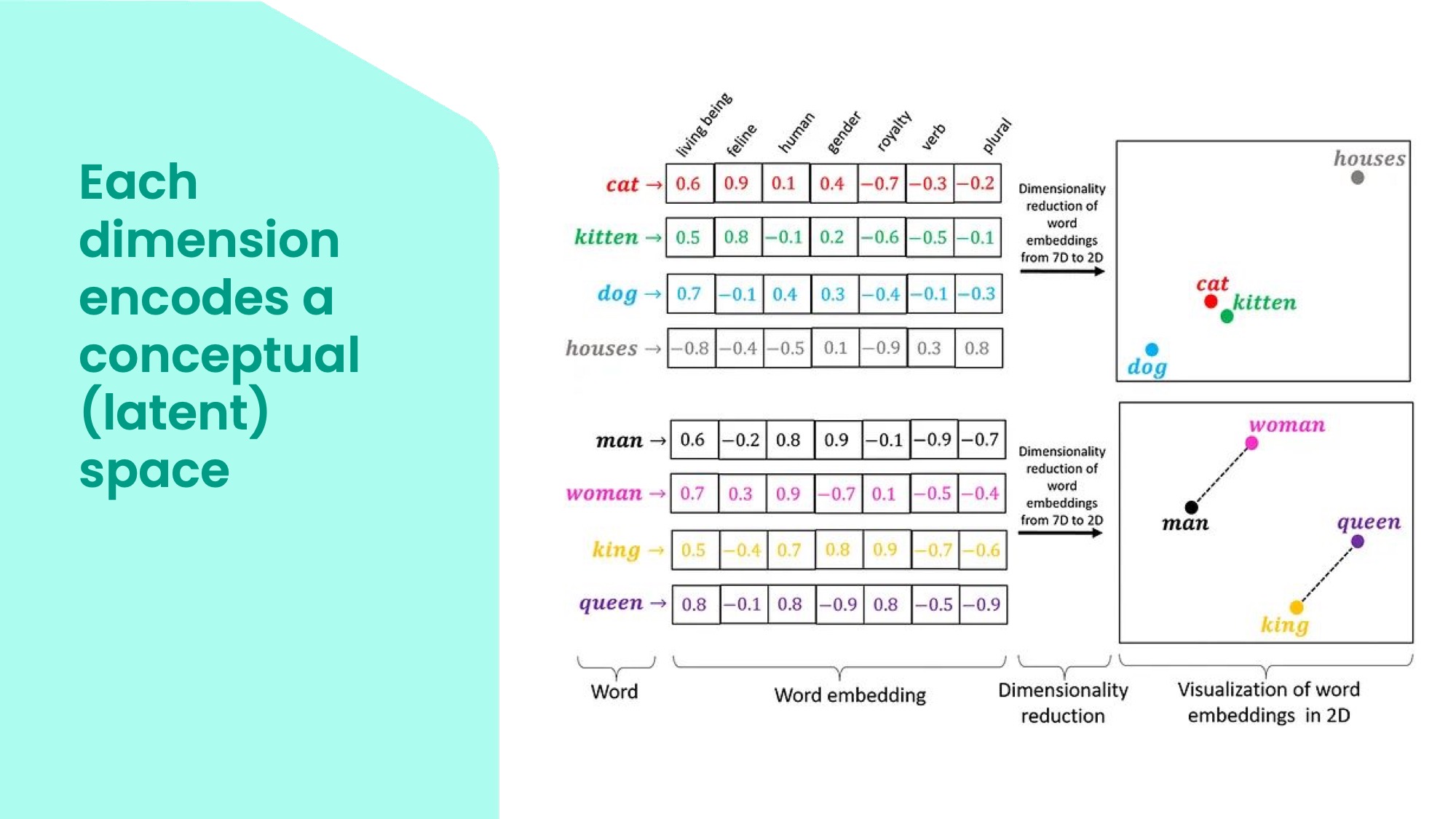

Embeddings are vectors in a high-dimensional space, which could have more than 1000 dimensions! Each dimension represents a latent or conceptual feature of the data.

For example, in this table, you can see some words and their embeddings in a simplified form. The top row shows some possible features, such as whether the word is a living being, how royal it is, how human it is, what gender it has, etc. The values in the matrix indicate how much each word has each feature. For instance, cat and dog are low on royalty, but high on living being and the cat is high on felineness. King and queen are high on royalty, human and gender. These are just constructed examples so the numbers might not always make sense, but the important thing is how each word can be placed on many different dimensions to end up in particular points in the conceptual space.

Embeddings are useful because they capture the semantic and syntactic similarities and differences between words, sentences, paragraphs, or even images. We can use statistical methods, such as principal component analysis (PCA), to reduce the dimensionality of the embeddings and visualise them in a lower-dimensional space. In this plot, you can see some examples of embeddings in a two-dimensional space. You can see that some words that are close to each other are related in one way or another. But because all the dimensions are collapsed in just two, words in clusters can be connected in very different ways.

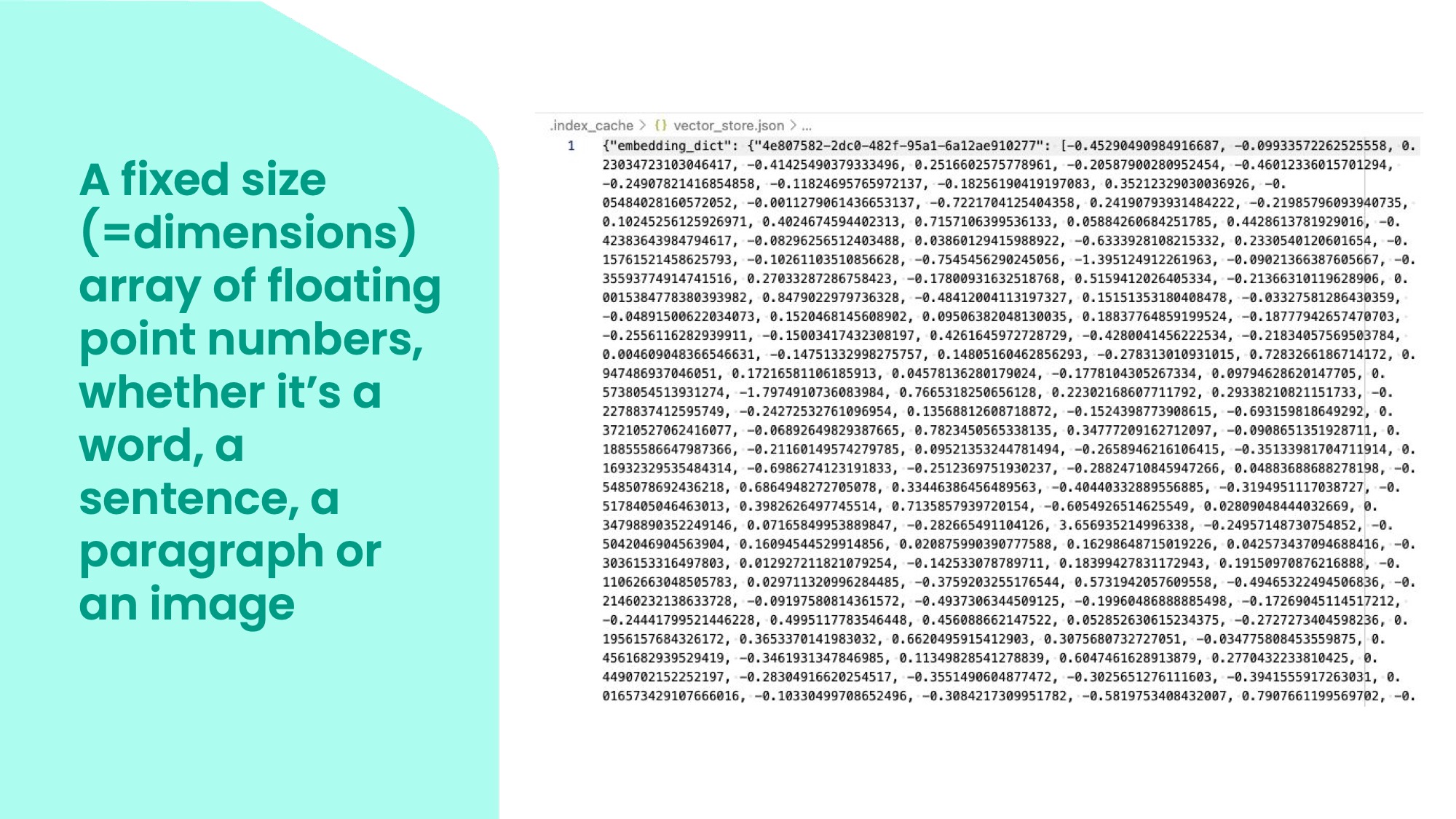

An embedding is a fixed-size array of floating-point numbers, where the size is the number of dimensions. It does not matter if the input is a single word, a sentence, a paragraph, or an image, the embedding process will always produce a list of the same size as a pointer in the high-dimensional space. This does mean that you need to be careful with try to embed too much text or an image that is too busy as the embedding will start missing details.

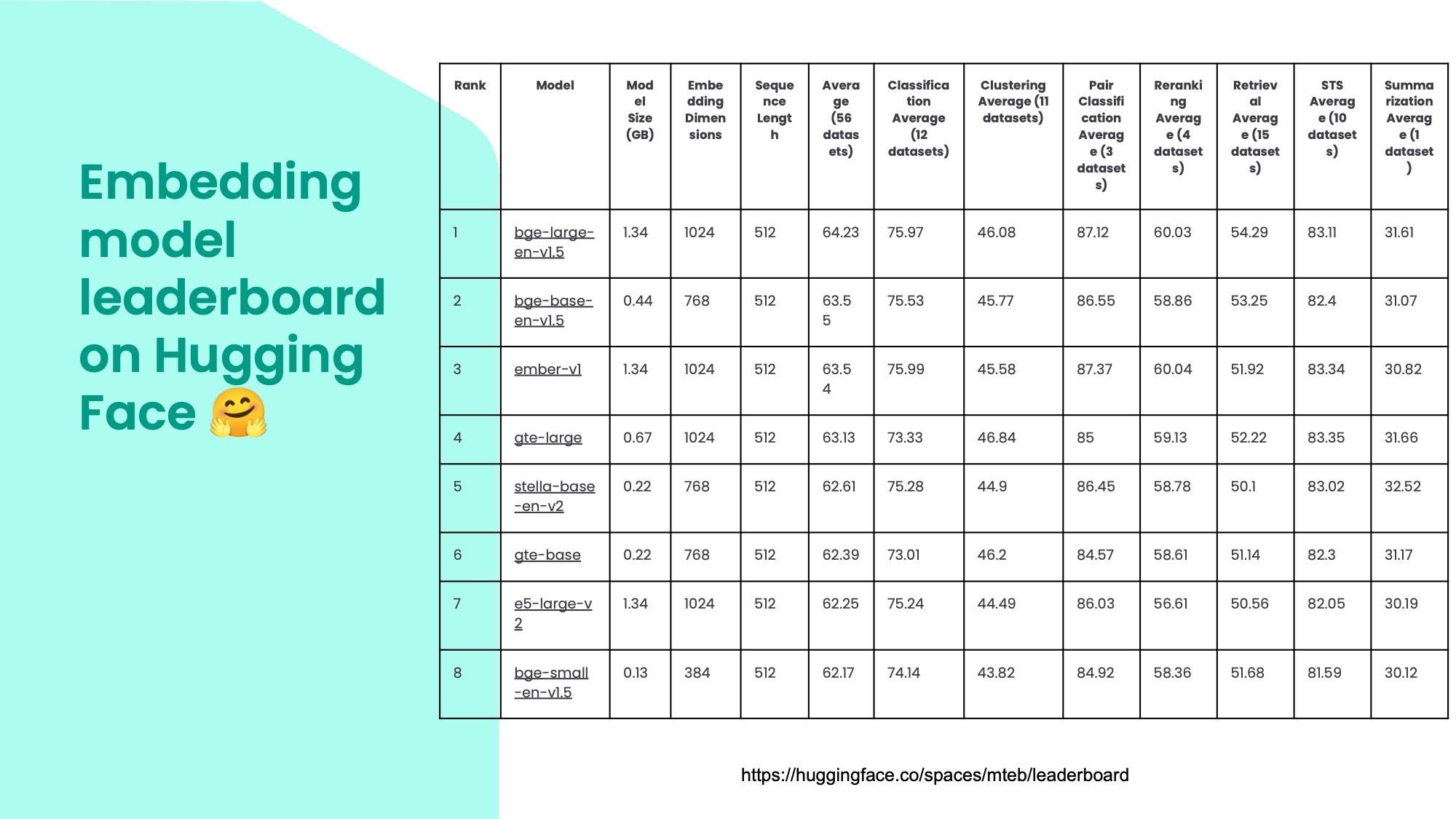

These are some embedding models from the Massive Text Embedding Benchmark (MTEB) leaderboard on Hugging Face. Hugging Face is a platform for machine learning models that is a bit like Github. I'm pretty sure it actually uses Git, if you look at the big, binary model files there's an icon saying LFS, which stands for Large File Storage.

You can see different models here and how they perform on various tasks. The BGE models are from Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence and they are amazing quality, especially for their size. The field changes very quickly though, so by the time you read this there might be even better models released.

You can also see the embedding dimensions in the fourth column. Bigger models have more than 1000 dimensions, but even the smallest one here, which is only 130 megabytes, has 384 dimensions and it’s still very impressive.

Hugging Face also has leaderboards for other types of models, such as language models. This is a great way to keep track of the state of the art in this fast-changing field. There are new models coming out every day in this open model space and the rate of innovation is absolutely amazing. That said, there are accusations that some people include the tests in their training data to cheat, so you shouldn't blindly rely on the results and test several models yourself for your particular use case.

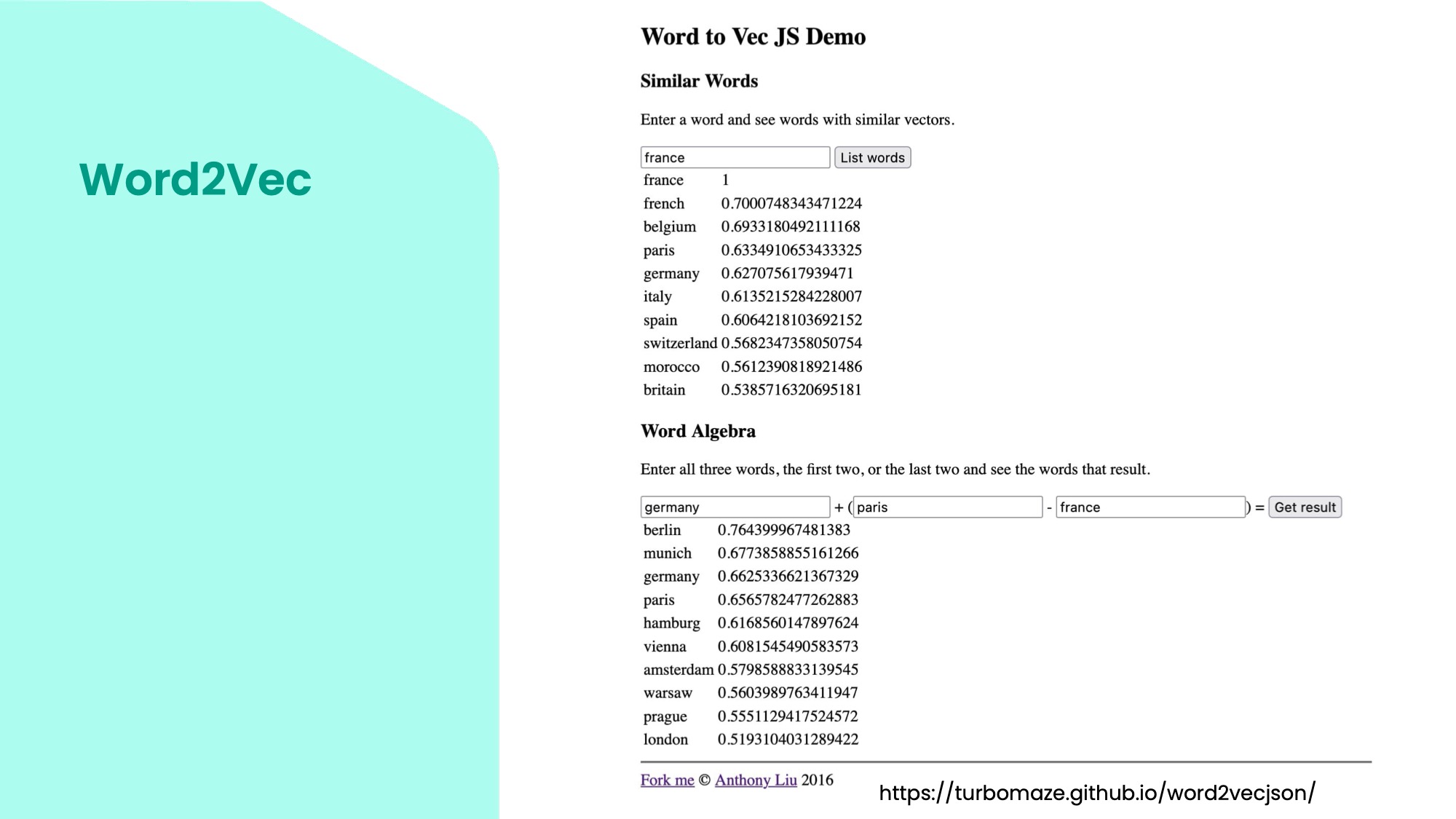

This is a simple demo of word embeddings using the model Word2Vec from 2013 by Google. It shows how words are represented in a relatively small multi-dimensional space. This one has tens of thousands of words. You can enter a word and see other words that are close to it in this space. For example, words close to France are French, Belgium, Paris, and Germany. You can see that they are related by language, country, or city. The interesting thing is that you can do algebra with these vectors. You can add and subtract words and get meaningful results. For example, if you take Germany and add Paris, but subtract France, you get Berlin.

In general, machine learning models don’t work with text as strings. Everything needs to be turned into numbers for the models to work with. This is because the models use matrix multiplication and other operations that work well on GPUs and computers in general.

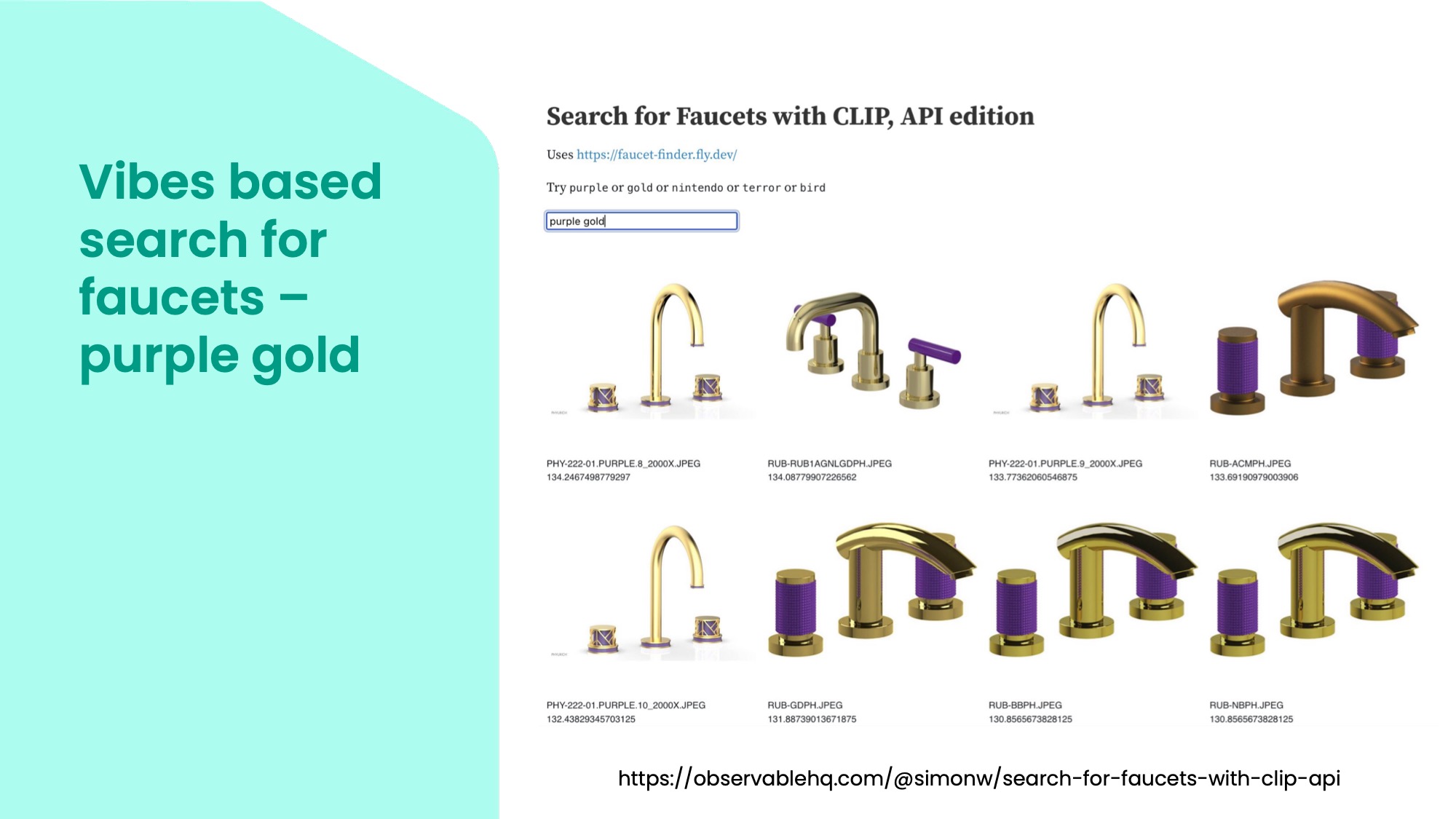

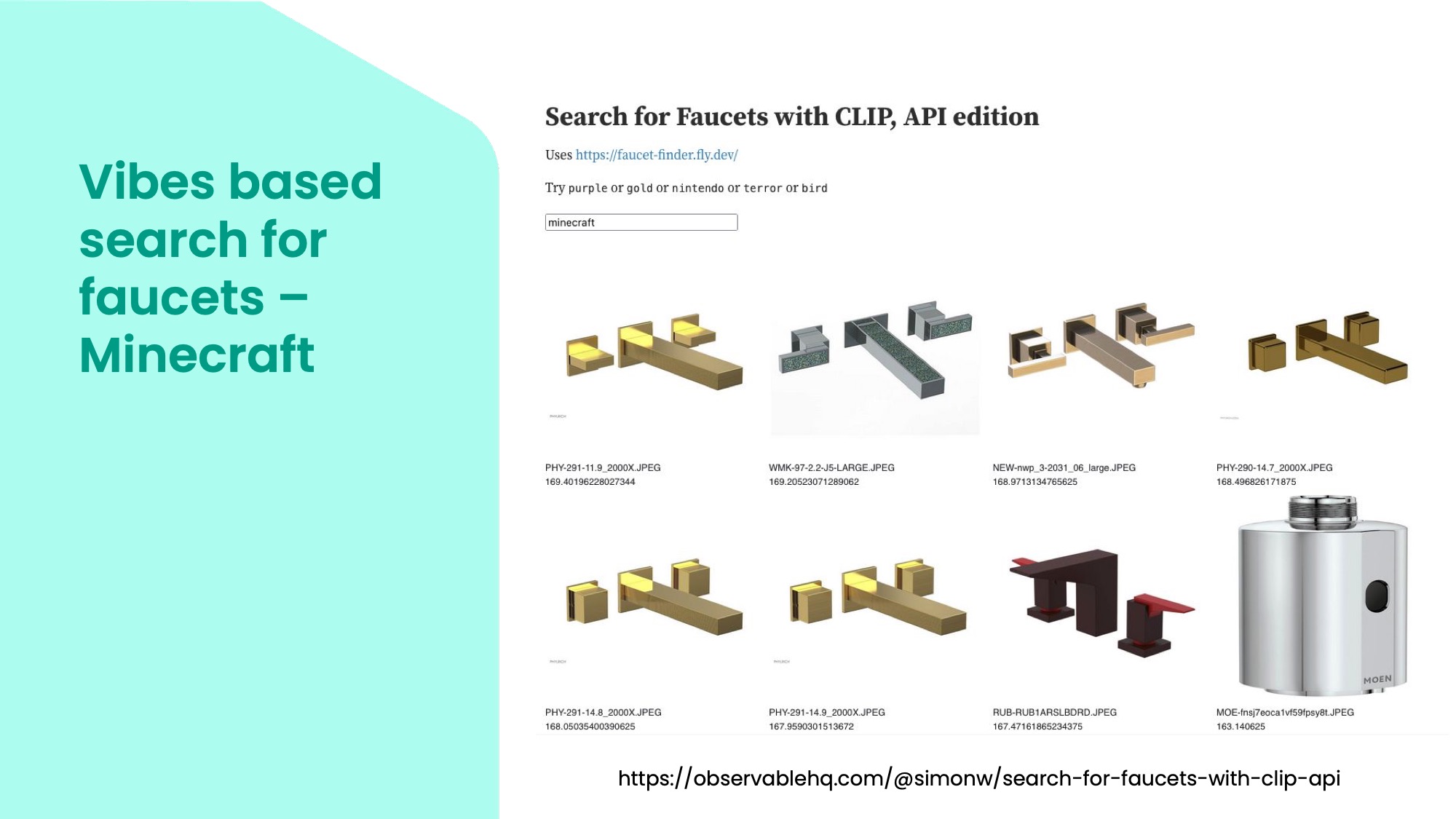

One interesting, direct application of embeddings is visual search. This faucet finder is an example of a search engine that uses CLIP – an actually open model made by OpenAI a while ago – that mixes images and words describing them. It does it by embedding both images and words in the same space so related ones are close to each other across modalities. This is also how DALL-E and Stable Diffusion can generate images from words: CLIP takes the words and embeds them, which the image generators then use to create the image that matches the words. So this is a simple example where you can enter words like purple or gold and get images that match them.

But you can also enter more interesting words like Minecraft and get images of blocky faucets. This shows that the model has a concept of Minecraft and can translate it to a different domain.

This is even more interesting: I entered Beryl and the model returned images of faucets with logos of the Red Dot Design Award on them. So it understood Berylness as design award winning lights and translated that to faucets. I'd say the rounded rectangular shapes also remind me a bit of the original Laserlight. This is so amazing and unexpected! It’s very hard to predict though what you will get from this kind of "vibes-based" search. It’s not based on keywords, but proximity in the conceptual space of the embeddings.

So to sum it up, you can use different embedding models to create a rich, semantic search very easily across various things like documents, articles, images, etc. But because it can be difficult to know what you will get, it's often a good idea to implement a hybrid search, mixing results from an embedding model (dense vectors) and a more straightforward keyword search (sparse vectors), and rank them into a combined result set. See for example the vector database Weaviate's approach for hybrid search.

Oh, on that note, if you are only working with a few documents or images, you can generate embeddings in memory or store them in a few JSON files and reload to memory later, but if you have a bigger set you want to search in, you'll need to use a vector database. This can either be a dedicated engine like Weaviate, Qdrant, Chroma or FAISS or an existing one with an extension like PostgreSQL with pgvector.

If you want to go deeper, make sure you read Vicki Boykis's ebook "What are embeddings". Its price (free!) betrays the quality of content that is written and structured so well!

Credits: Simon Willison for his work on various tools and explanations, his blog post on embedding in particular.