- Authors

This article is the second in the series Building applications using embeddings vector search and Large Language Models. In these blog posts I'll explain these concepts and the process of building a semantic document search pipeline. These materials are based on an internal documentation search tool and a talk I gave about it at Beryl.

The previous post was Understanding embeddings and how to use them for semantic search.

This post will help you understand large language models (LLMs) by giving a quick overview of their history, offering various mental models to describe them, and practical details about using open LLMs.

First, let me give you an overview of large language models.

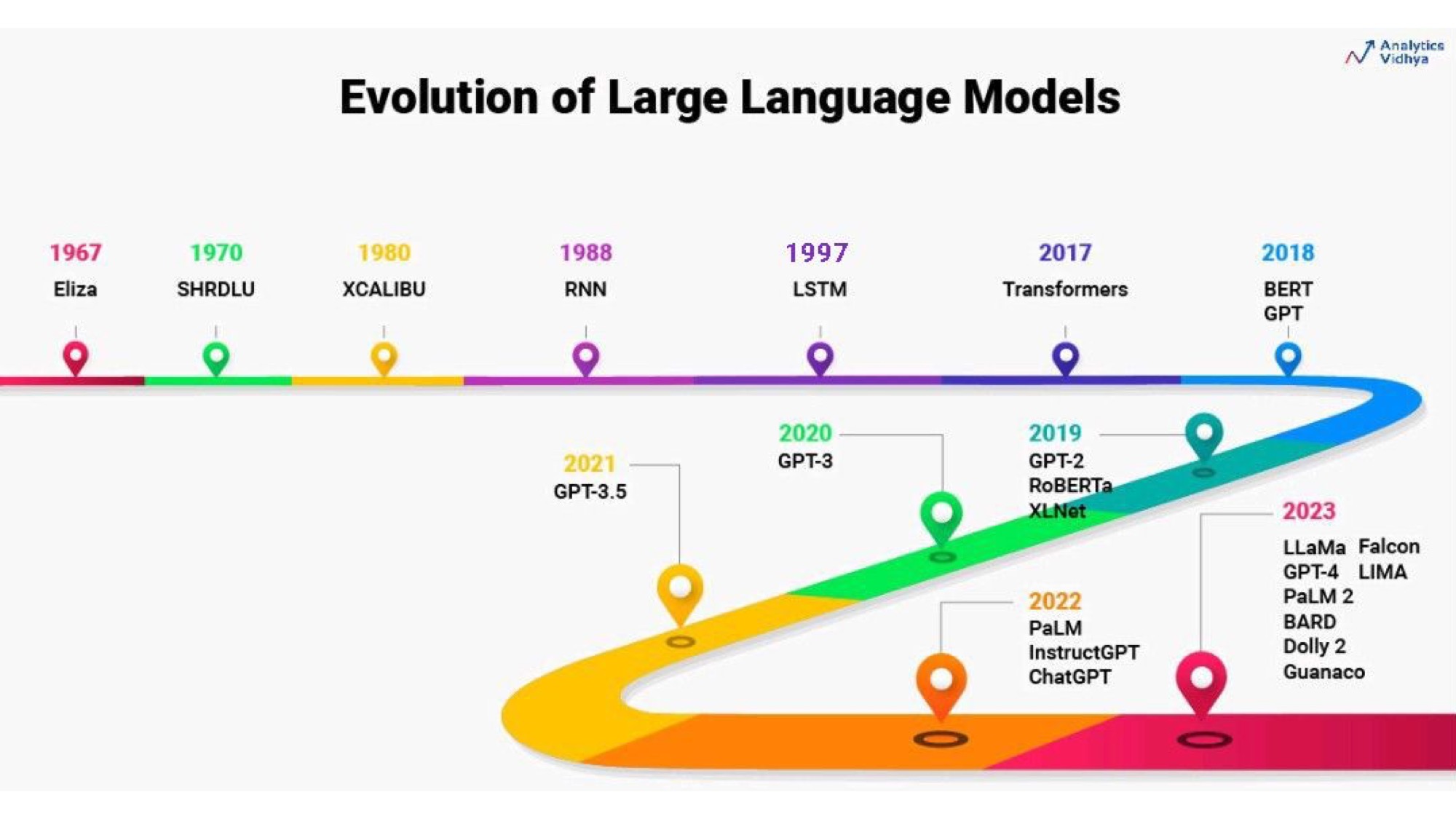

Language models have evolved a lot over time. One of the early experiments was Eliza, which was a simple script that pretended to be a therapist. It asked simple follow-up questions like “That's very interesting, can you tell me more?” and people would open up to it. The creator of Eliza wanted to show how superficial the program was, but he ended up being surprised that people found value in it. But Eliza was not a real language model, it was a pattern matching script trying to pick key words to ask questions about.

The big change happened in 2017 when Google Brain published the Transformers paper. This started the era of BERT, GPT, and other contemporary language models. Until 2022, most of the models were from Google and OpenAI, but this year (2023) the first open large language model was first leaked and then officially released by Meta. It's called Llama and it wasn't really open source as they haven't published too much details on how to train it. But since then, there have been many open models where the dataset or at least parameters are available too. This is interesting because you can take a model and finetune it to modify it to suit your needs. So this year has been very exciting for people who enjoy tinkering with models on their computers without using an API.

An important thing to consider when choosing a model is what it is trained for. The base models, like GPT-2 and GPT-3, were not very exciting. Most people didn't care too much about them. They were just bigger and slightly better than previous models, but finishing sentences in cleverer ways wasn't that useful by itself.

The big breakthrough was ChatGPT, which was released one year ago (at the end of 2022). It had a feature called instruct tuning, which means that it could follow a dialogue and understand instructions. This was a big difference because you could tell it what to do and it could actually follow and do it. It wouldn't just complete your sentence or generate more sentences from what you started. It didn't need a few-shot prompt, which is when you give it an example of what you want and it tries to replicate it. You could just give it an instruction and it would (mostly) understand and execute it right away, so zero-shot. This opened up a whole new world for building tools.

So what is a large language model?

There are different ways to answer that, but one way people put it is that it is a very smart autocomplete or a stochastic parrot. So on the surface it is not very different from the keyboard autocomplete, except that it is much bigger and has more words in its memory. It can generate not just words, but sentences and paragraphs. But ultimately, they aren't that far and actually, I wouldn't be surprised to see tiny LLMs being built into smartphone keyboards soon.

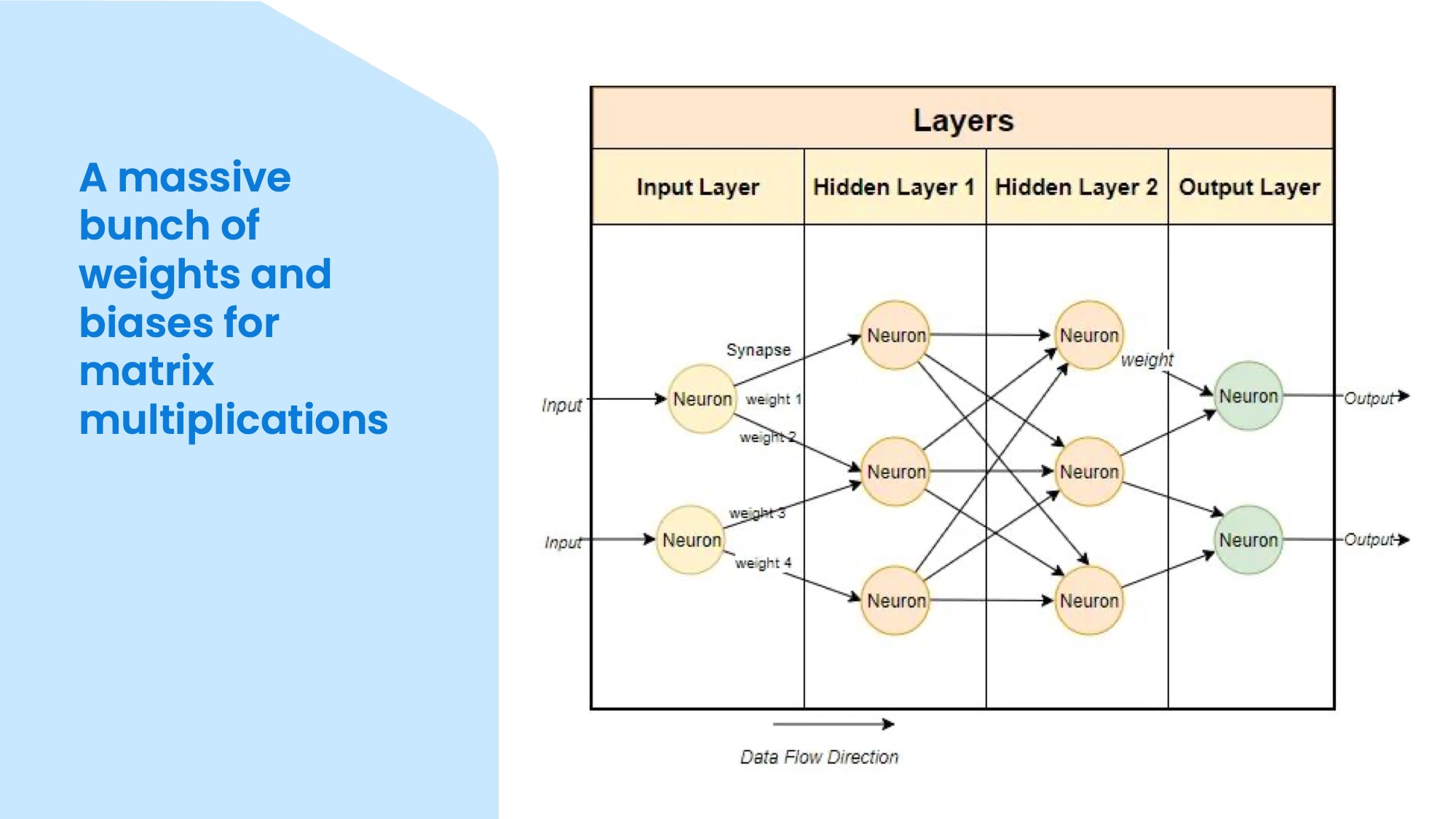

Another way to answer the question is to say that it is a huge neural network with a lot of weights and biases that do matrix multiplications. This means that it takes an input, which is a list of numbers, and passes it through a network of nodes, which modify numbers. So the input flows through the network and activates different nodes, and at the end you get an output, which is also a list of numbers. These numeric inputs and outputs are called tokens and they need to be converted from text.

You can also think of it as a function that takes some input text and some parameters, such as temperature, random seed, and top-k, and returns some output text. The parameters affect how the function behaves. The temperature controls how many words it will consider as candidates for the next word. If the temperature is zero, it will always pick the most likely word. If the temperature is high, it will pick a random word from a larger pool. If the random seed is the same, you will get the same output every time. The top-k controls how many words are in the selection pool for each next word. If the top-k is low, it will only consider the most likely words. If the top-k is high, it will consider more words.

These parameters are important because they affect the quality and creativity of the output. If you want the output to be more creative, such as when you want to write a poem, you need a higher temperature and top-k. If you want the output to be more accurate and consistent, such as when you want to use it in a tool, you need a lower temperature and top-k. You need to tweak these parameters to get what you want from the model.

This is LM Studio in the screenshot, my current favourite application to download and try basic chats with open language models. It uses a local model that I downloaded and you can see some stats at the bottom. I just entered a simple sentence completion task: “The capital of Congo is”. The model returned “Kinshasa” as the answer.

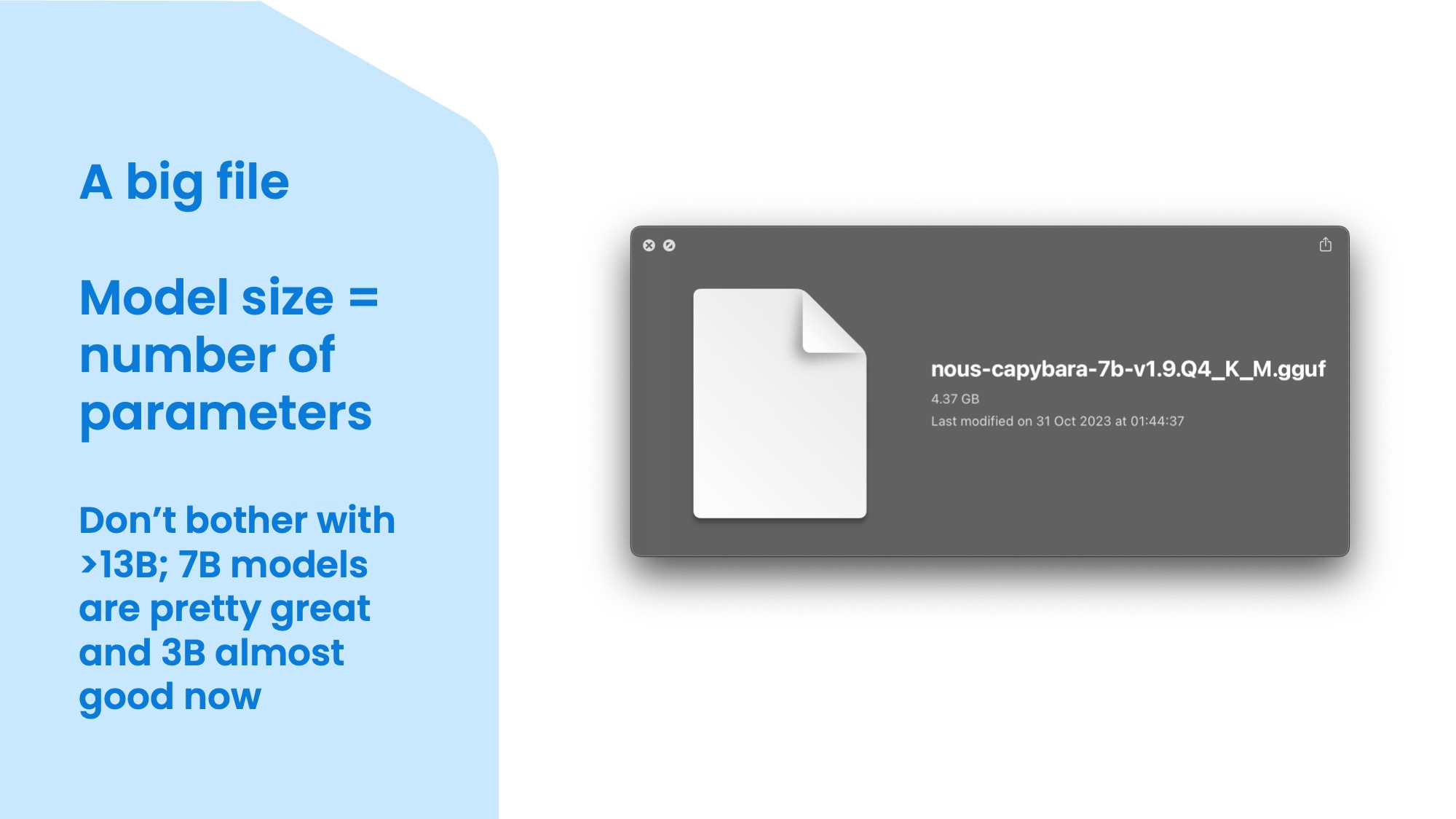

A model is also a big file, the size of which mostly depends on the number of parameters. Parameters are numbers that represent the connections between the nodes in the neural network. The more parameters, the bigger and more powerful the model. This is a 7 billion parameter model that is quantised to 4 bits. It is 4.37 gigabytes so it's not that big, but it is very impressive especially for this size. The human brain has about 86 billion neurons, which are similar to nodes, but apparently they are much more efficient than current models. The biggest models have hundreds of billions of parameters, but they are not open source and they require a lot of computing power and memory. I think 7 billion is a good size for simple tasks as part of a pipeline like Langchain or LlamaIndex, but there are even some promising 3 billion parameter models emerging. However, they are not yet very good at following instructions, which is what you need for building more complex and reliable tools. If you have at least 32GB memory available (either VRAM on a dedicated GPU or unified RAM on a Mac) you should also try the Mixtral model (or finetunes) as it generates responses at a similar speed as a 12B parameter model would, but has capabilities of a much larger model due to its Sparse Mixture-of-Experts architecture.

So a large language model takes some input text and generates some output text based on the probabilities of the next word, one by one. It is not an oracle that knows everything and if you try to use it like that, you'll be disappointed. Think of it more like a calculator for text (thanks Simon). It can do almost anything with text, such as summarising, answering questions, extracting facts, naming things, rewriting, and changing style. You can also use it to name things, which as we know is the hardest thing in programming. A useful trick is to ask it for 20 names and then pick the ones that are not obvious or boring. You need to ask for a long enough list so it needs to scrape the barrel a little bit and make more effort.

It can also work with different formats, such as JSON or binary files. You can give it a binary file and it can guess what it is, especially if it's a big model like GPT-4 that came across it in its training data. It can say, “Oh, that's a MIDI file!” and then you can give the file the right extension and it will work. If the header isn't super obvious, it would take a long time to figure out what format a binary file is by yourself.

One of the people who is doing a lot of experiments with large language models is Simon Willison. He is a bit of a web celebrity in the AI space, talking on TV and giving opinion in news articles, but not without a good reason. I learnt a lot from his articles and talks, there's a fair bit of material in this talk from his writing. He also created a command line tool called llm that is compatible with Unix pipes. You can pipe some text to the tool and it will do something with it using a language model. This is very convenient because you don't need to rememeber how to write sed or awk commands and how Mac OS has subtly different syntax than GNU versions. You can just pipe something to the tool and ask it to do something with it. For example, you can pipe a bunch of text and ask it to find all the files that have a name that's in the topic. You don't need to choose which tool to use or remember the commands. You can just give it some text and get some reasonable output. Of course, it might get it wrong or just make stuff up, so it's more for exploration than building something solid you'd rely on for operating hospitals.

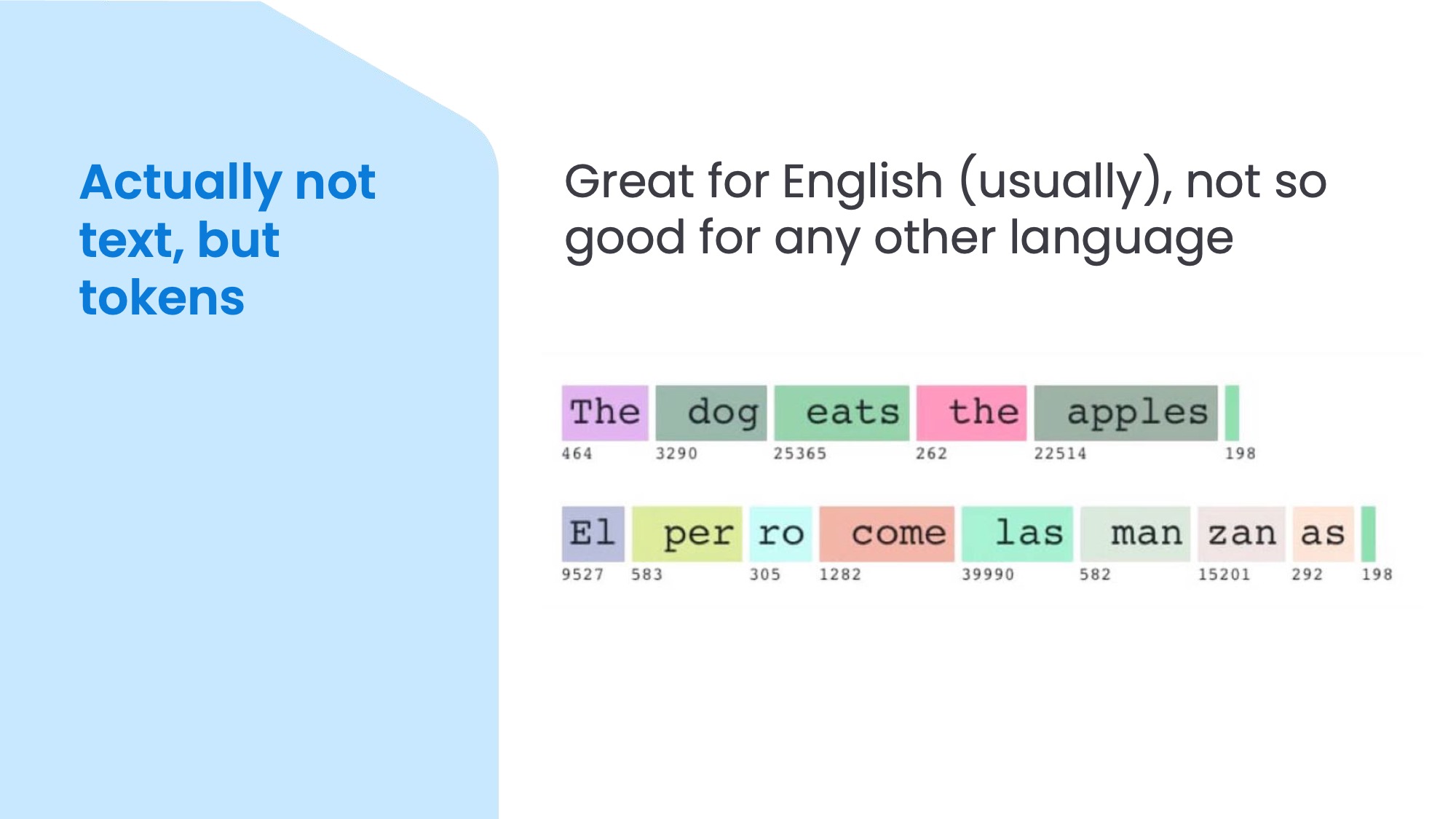

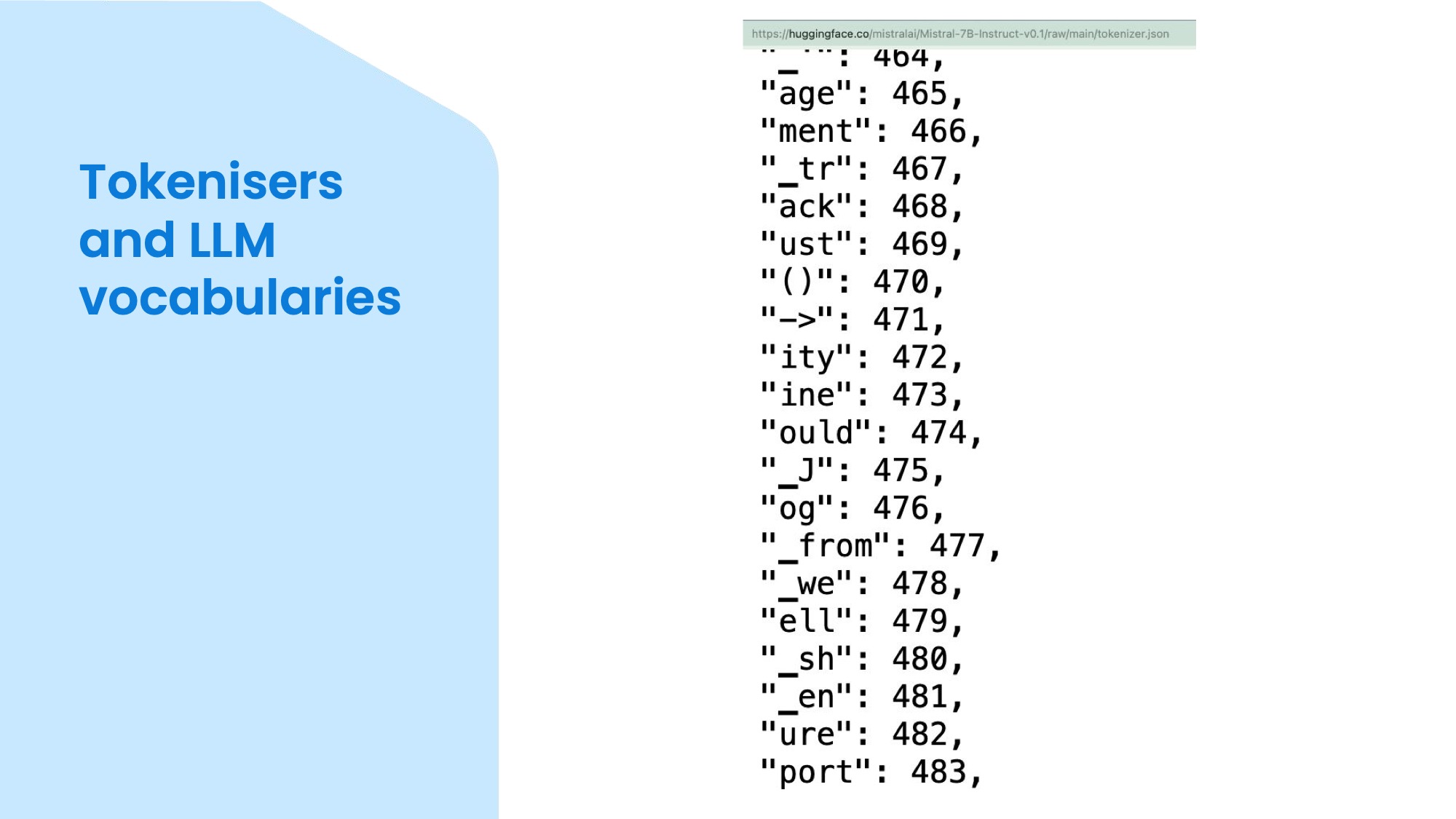

But actually, the input to LLMs is not text, but tokens. Internally, these tokens are represented by numbers. For example, some of the 7B open models I checked have a token vocabulary of around 32,000. The most common words in this vocabulary often include a leading space, because that makes it faster and cheaper to process than having a separate token for the space. These words in the top are mapped to one token each. However, for languages other than English – like Spanish in this example – the tokens may be more like syllables. So, most text in Spanish would require more tokens than the same text in English. This matters if you use hosted APIs, such as the OpenAI API, which charge by the token. This is more of a problem if you're building something for languages other than English or text with a lot of special characters, but unfortunately to change the tokeniser (and training data language) you need to pretrain a model from scratch, so not an issue you can easily do something about.

The token vocabulary is often uploaded to Hugging Face as a separate JSON lookup table called tokenizer.json. Together with tokenizer_config.json it's possible to re-implement the tokeniser outside of the model. In this screenshot on the left, you have the text, and on the right, you have the corresponding token number. Some models are bilingual or multilingual, and they have tokens for both English and other languages, or non-Latin character sets such as Chinese, Cyrillic, and emojis. Depending on your use case, this kind of model may be more suitable, but most models are still mainly English.

I was curious about these differences, so built a tool in which you can type any text, see how it would get tokenised, and compare several models side-by-side: Online LLM Tokenizer

Just for completeness, even tokens themselves aren't directly fed into the models, first they get mapped to an input embedding vector and then these are given as inputs to the model. So for example “pumpkin“ becomes [12048, 7510] tokens and those become [[-1.43, 0.65, -0.99, 1.85, ...], [1.3, -0.85, 0.99, 0.58, ...]] input embeddings. And if you want to know what happens with these inside a transformer model and how you get some text back, read this article.

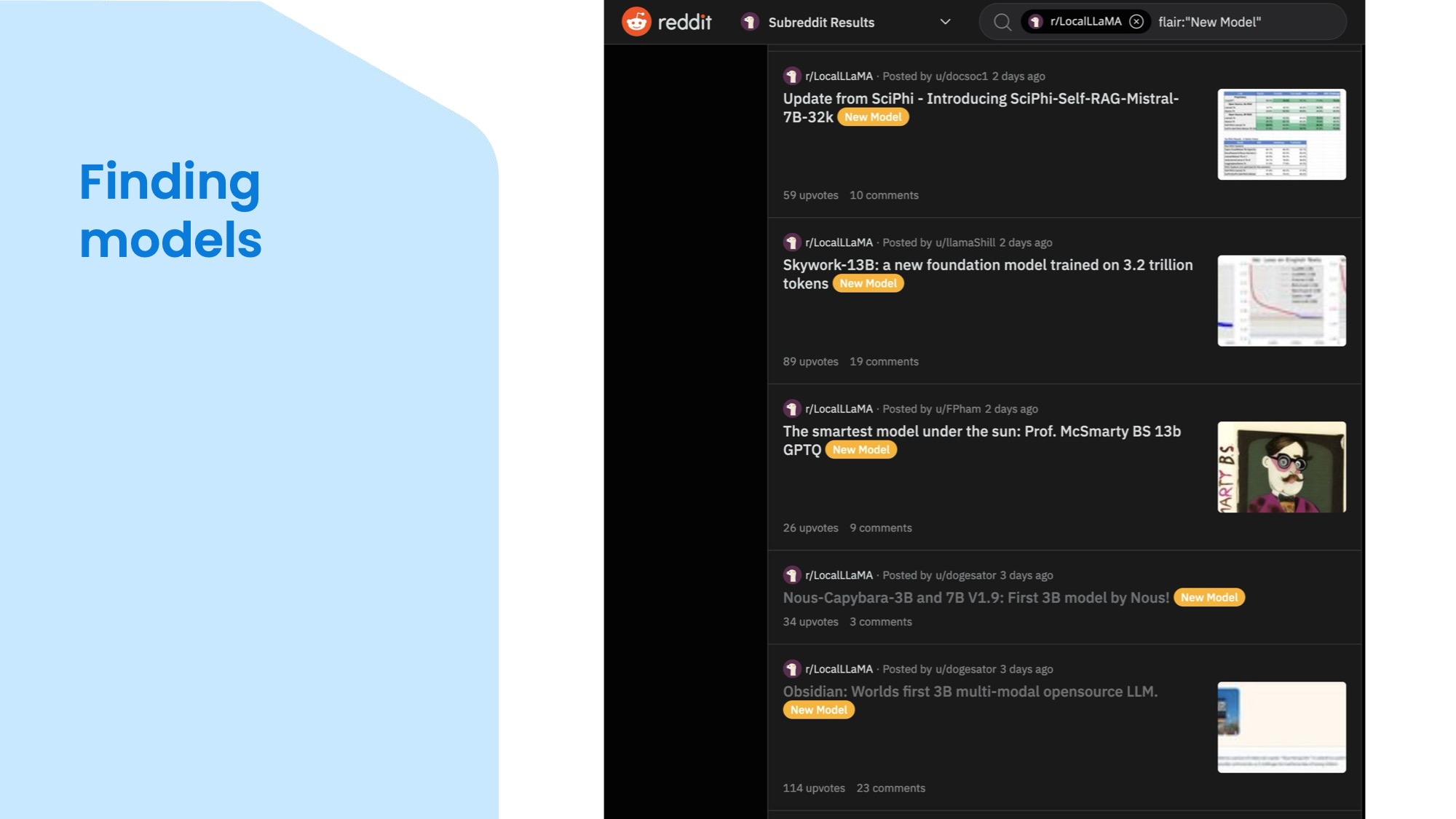

So you decided open LLMs sound great, would be cool to try one, but how do you choose one of the millons available just on Hugging Face? There are lists on Hugging Face itself showing you which models have been most popular over time and which ones are trending, but I often find the model cards a bit lacking to understand what a model is really good for and often its abilities are vastly overstated. So one alternative way to find out about new models is to visit the subreddit LocalLlama, where people post their creations and share the papers and the motivations behind them. For example, the bottom post is about Obsidian, a three billion parameter multimodal model that can handle both text and images. The one above, Capybara is a family of small model from the same research group Nous. You'll find a lot of animals in model names, which first sounds a bit ridiculous, but actually can give you some idea about the dataset and base model once you start understanding the patterns. But most importantly, you can click through and read a discussion with various people sharing their experiences in the comments, so you can get quick idea if the model lives up to the author's hype and what kind of use cases people found the model useful for. For example, a model for understanding and generating code will be quite different from one finetuned for role-playing different characters and generating stories in those roles. You'll also find out which inference library supports the model based on the architecture and hardware to run on.

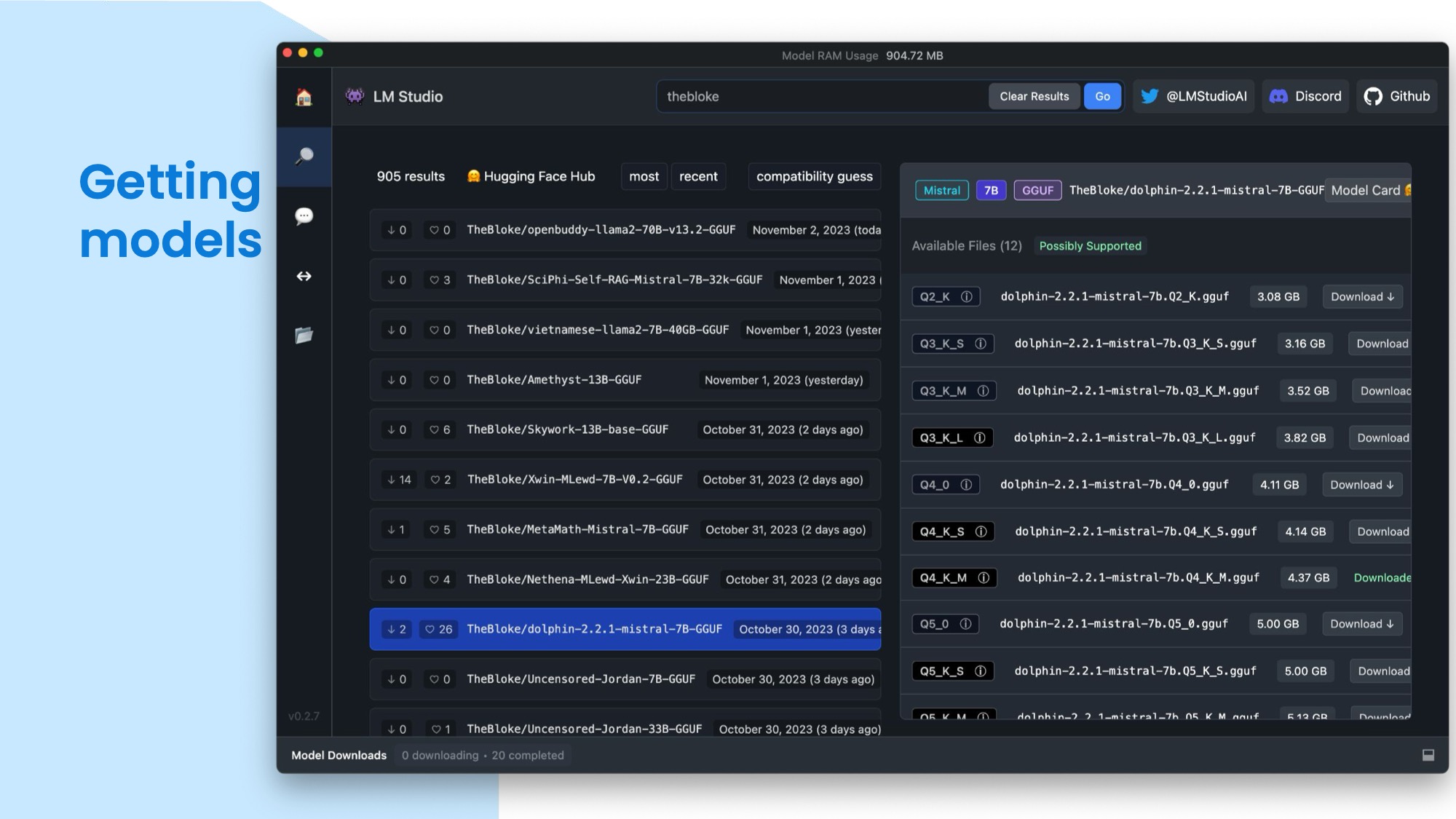

But how do you get these models and use them in your own applications? One option is to directly download them from Hugging Face or you can also use a native app like LM Studio to search and download from it. You can see the different models and their versions on the left, and choose the quantisation level (I'll discuss these in a minute) you want to download. Then you can use the model in your code or in LM Studio itself, which uses Llama.cpp for inference. You can chat directly in LM Studio or let it host a model in a web server. The default download directory is a bit long and hidden, so I have mine set to ~/.models to make it easy to reference from code in applications or in the Terminal.

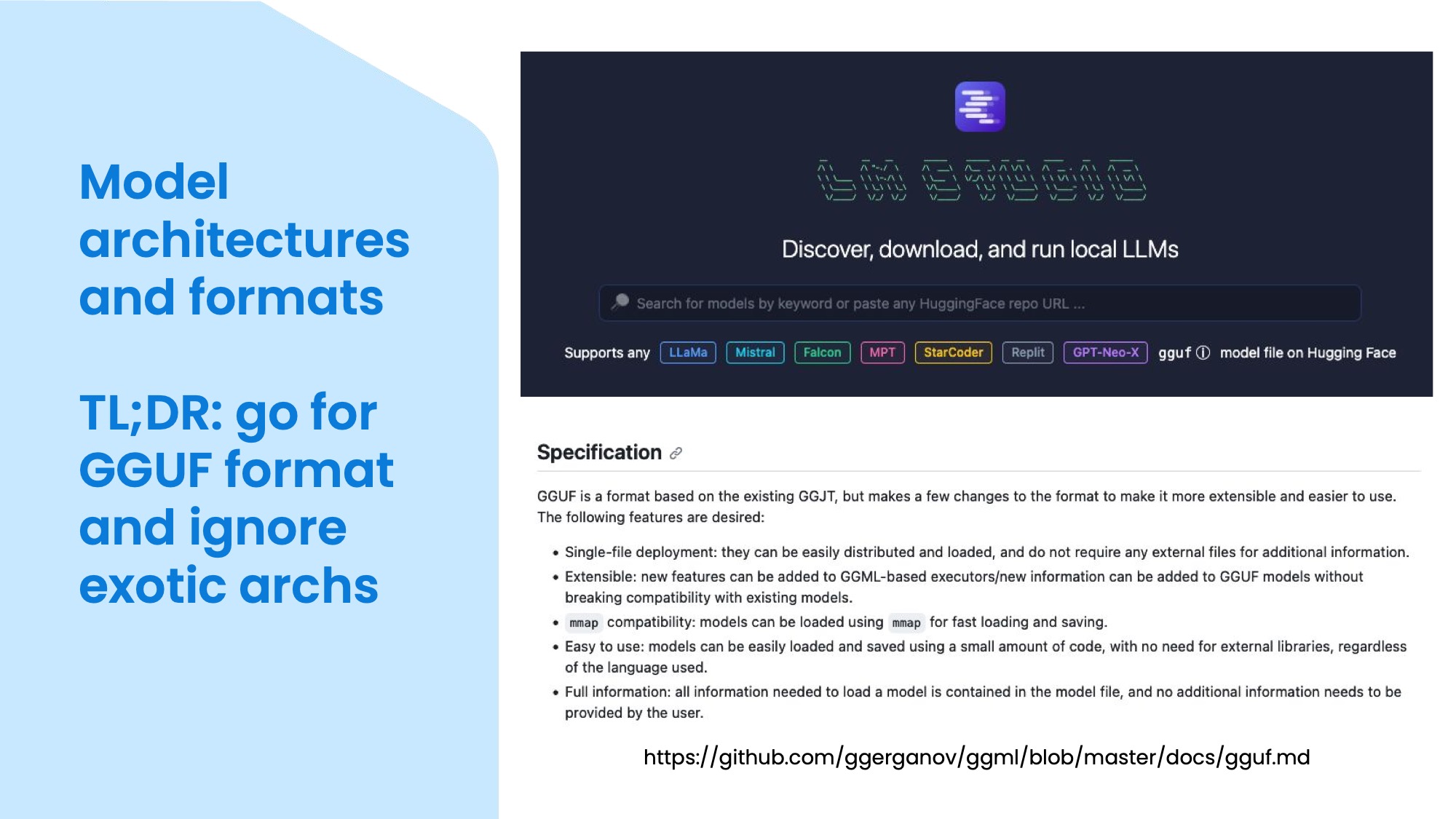

However, there are still some challenges when it comes to choosing a model. One is that there are many different model architectures, such as LLaMa, Mistral, Falcon, StableLM, GPT-Neo-X, and so on. These architectures have different designs and capabilities so the inference libraries need to specifically implement each. Another challenge is that there are different model formats, such as ONNX, PyTorch, TensorFlow, and so on. These formats have different ways of storing and loading the model parameters, and you need to have the right tools and libraries to work with them. This can be annoying and time-consuming, especially if you have to deal with hundreds of Python dependencies to support each and to be able to quickly swap them for testing.

To solve these problems, there is a model format called GGUF, which probably stands for Georgi Gerganov's Universal Format after the founder of Llama.cpp. This format is designed to store not only the model parameters, but also tools and metadata, such as the tokeniser, the prompt format, etc. This makes it easier for the inference library to know how to run the model without you having to worry about the details. GGUF is a binary format optimised for loading the model into memory directly using mmap(). GGUF is becoming more popular and widely adopted, and I usually prefer to use models that have a GGUF conversion. If a model isn't yet converted, I usually just wait until someone does it as it's also a good indicator if anyone is excited enough to bother converting – or if it's a new, unsupported architecture – implementing in Llama.cpp. You can see a snippet from the specification for GGUF at the bottom of this slide.

I mentioned Llama.cpp a few times so owe you a more detailed explanation: it's a pure C++ implementation of the LLaMa Python library to load a model in memory and let you run inference without any dependencies, aimed mostly at consumer-grade hardware, specifically Apple Silicon Macs. So the project is very performance focused while keeping the footprint small. Even if you don't have a Mac or a GPU, if you have a recent CPU you'll be able to get usable speeds out of smaller models and Llama.cpp will use whichever is the fastest instruction set (AVX2, etc) your CPU can support.

This is a big difference from using something like Pytorch and Python in general, where you need to install lots of libraries and the language itself isn't that fast – though of course the ML libraries achieve a decent speed using native extensions, but those make installation even more complicated. So unless you want to train or finetune models, I don't recommend getting into the weeds with Python directly interacting with the model. That said, you can somewhat have your cake and eat it by using the llama-cpp-python library that is a relatively low dependency library running llama.cpp as inference backend. With this library you can either run an API that is more sophisticated than the basic one built into Llama.cpp or use the inference in Python code directly to build tools on top of LLMs.

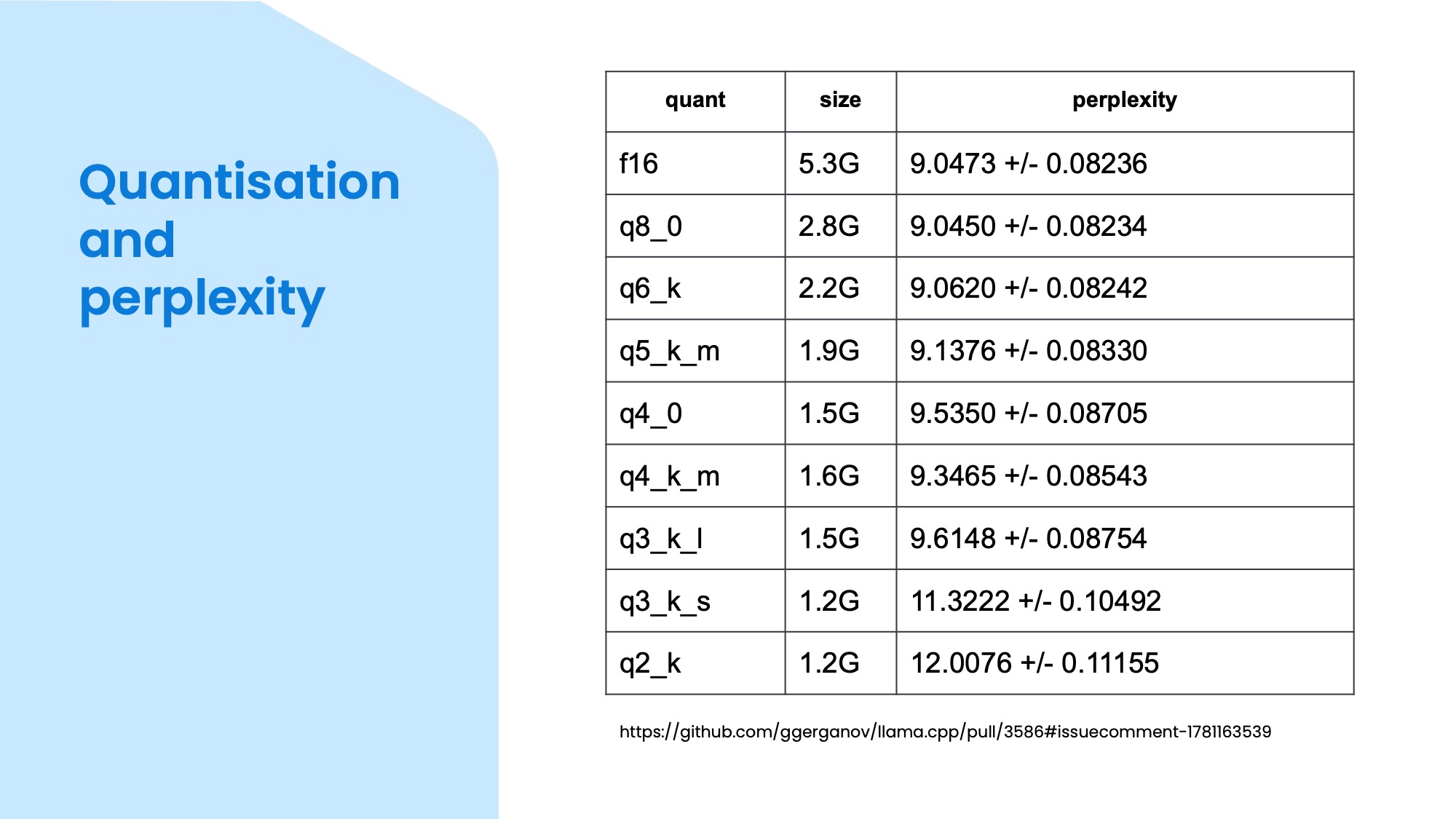

I mentioned quantisation a few times, it is a really cool trick for compressing models by decreasing the accuracy of the vectors. What's amazing about it is that you can actually go down an incredible amount before the quality of the models generation starts to noticeably worsen. And when it does, it happens gradually, so it won't just suddenly flip into nonsense, but will be a bit less coherent and you can see which level still does the job you need it for. What's even better is that the quantised model is also faster to do inference! (Technically it is a bit slower to run the inference itself because the need to de-quantise the weights first, but the small size means it's faster to load and access the model in memory which is often the bottleneck.)

This table shows the size comparison between various quantisation levels. As a general guideline, you can expect almost full fidelity around 6-8 bits for small models like 3B parameters, 4-5 bits for 7B and 13B models and 3-4 bits for larger ones like 30B or 70B. The values in the perplexity column means how different or confused is the model ouput compared to a reference one, so lower numbers are better.

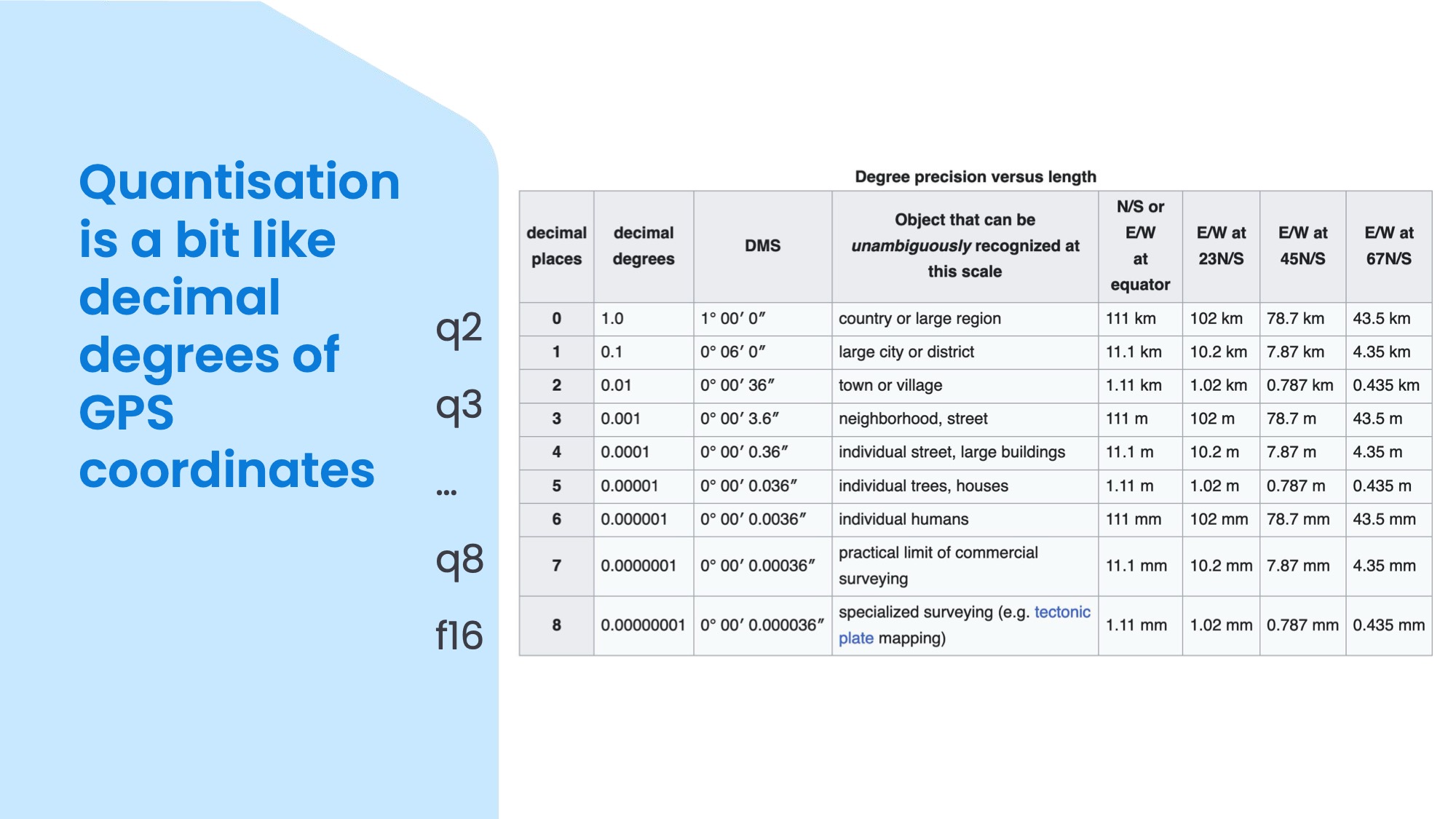

To give you a metaphor for quantisation, if you are familiar with GPS coordinates, you might have noticed that there's a varying amount of numbers after the decimal point in the latitude and longitude values. In this table you can see that 8 decimal places gives you millimetre precision on the surface of the entire planet which is pretty cool, but rarely needed. To find a building for example, 4 or 5 decimal places would do, depending on whether it's a shed or library you are looking for.

I hope this practical overview gave you a good idea about open LLMs and how to use them! If you have any comments or questions feel free to post below!